Today, in both UN and World Bank reports, the Middle East and North Africa region scores the lowest of any global region when it comes to employment, with a rate of 10.6% across the whole region. Unemployment is particularly striking among women populations; in fact, only one in three young Arab women between the ages of 23 and 29 participate in their country’s labor force. As a consequence, female labor market participation (LMP) in the MENA rates at a level of 31%, which is extremely low compared to other regions in the world such as 43% in Latin America, 48% in South Asia, and 68% in Europe and Central Asia. Moreover, the gender gap is quite homogenous across all Arab countries, with female LMP rates at 24% in Egypt and 27% in Syria. Women’s employment is, therefore, one of the major challenges the MENA region is facing today.

Economic factors that hinder women’s employment

One of the main dynamics behind the low female participation rates in MENA is the institutional structure of the MENA labor market today. First, because structural adjustment in the MENA region has, in general, resulted in a de-feminization of the private sector. Women MENA workers are mostly concentrated in the public sector. As a matter of fact, 82% of the total workers in the public sector in Algeria today are women, 52% in Jordan and 58% in Egypt. However, the public sector’s poor future growth prospects means women are the first to suffer from the situation, putting them in a marginal and vulnerable position.

The very nature of MENA economies and the specialization of MENA markets contribute to hinder female labor supply. In fact, most of the MENA region’s economies are oil-based and, therefore, only offer a few jobs which tend to target men. Out of the twelve member countries in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), eight are MENA countries, notably Libya, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait and Qatar. These figures contribute the needs scheme in which fewer formal labor market positions mean fewer chances for women to acquire the status of ‘secondary workers’ needed foremost when no males are available.

The very nature of MENA economies and the specialization of MENA markets contribute to hinder female labor supply. In fact, most of the MENA region’s economies are oil-based and, therefore, only offer a few jobs which tend to target men. Out of the twelve member countries in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), eight are MENA countries, notably Libya, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait and Qatar. These figures contribute the needs scheme in which fewer formal labor market positions mean fewer chances for women to acquire the status of ‘secondary workers’ needed foremost when no males are available.

Ultimately, MENA women today are also discriminated against – when it comes to market hiring preferences where male and female-owned firms in the region tend to hire, on average, far fewer women in comparison to world averages.

To illustrate, in MENA male-owned firms, only 22% of total workers are women, in comparison with 42% in East Asia, and 30% in South Asia. More strikingly so, the situation is even worse when it comes to female-owned firms: only 25% of MENA workers in female-owned firms are women, compared to 48% in East Asia, 39% in Latin American and 34% in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Conversely, if slow-to-change institutional patterns contribute to undermine women’s employment in the MENA, women’s unemployment itself also undermines the whole economy of the region at the macroeconomic level.

In this sense, integrating MENA women in the economy would be of double-benefit: it will reinforce the role of women in the society, and stimulate the economic activity of the region.

Low female participation rates today result in a loss of 25% of the average family revenues and, on a macroeconomic level, in a smaller rate of economic growth of 0.7 percentage points a year. As a matter of fact, women’s high unemployment rates deprive the region’s economy of the labor and skills of half the population, which is one of the main explanatory factors for relative Arab economic backwardness: “Women are indeed the Arab World’s unutilized and unrecognized human reserve”. Hence, women participation in the labor market is a pre-condition to the development of the entire Arab region.

Likewise, an important aspect of women’s empowerment concerns their economic participation

In this sense, integrating MENA women in the economy would be of double-benefit: it will reinforce the role of women in the society, and stimulate the economic activity of the region. Therefore, because women’s participation in the economy is an as integral part of their empowerment as well as a pre-condition to the human and economic development of the whole region, it has become a major imperative and challenge for the MENA region today.

Cultural factors that preserve the gender gap

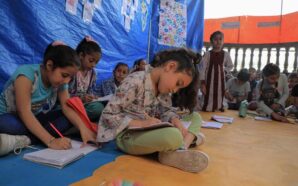

Cultural barriers and obstacles also contribute to reinforce the gender gap, thus constraining women’s economic participation. First and foremost, the persistence of the traditional gender stereotype contributes to the reproduction of inequality in the society. Highly resistant norms and perspectives still give women the primacy in reproduction and familial roles.

Cultural barriers and obstacles also contribute to reinforce the gender gap, thus constraining women’s economic participation. First and foremost, the persistence of the traditional gender stereotype contributes to the reproduction of inequality in the society. Highly resistant norms and perspectives still give women the primacy in reproduction and familial roles.

Case in point, women’s labor participation in the MENA reaches its peak earlier than in other regions of the world, with the peak occurring between the ages of 20 and 24, after which it starts decreasing. Hence, with the peak corresponding roughly to the age of marriage and early childbearing, this implies that marriage in the region entails other kind of responsibilities, which oblige women to renounce their jobs.

In her work, Roksana Bahramitsva explains that within the traditional model of marriage, men are defined as the breadwinners and women as the homemakers, thereby setting a priority for domestic and reproductive roles for women, which then severely limits their post-marriage employment and career growth prospects.

Another factor undermining women’s employment in the region is their de facto unequal access to education. Today, about 40% of women across the Middle East region are illiterate, with slight variations from one country to the other. And because women are not given the same educational opportunities as men, far fewer actually enter the workforce.

Another factor undermining women’s employment in the region is their de facto unequal access to education.

In fact, schooling also has a positive effect on both reproductive and employment choices. Research shows that 66% of women who finish secondary and higher education use contraceptives and end up with a 1.9 child average, and only 44% of women with no education make use of contraceptives and subsequently end up raising 4 or more children.

The laws also play a key role in tackling the issue of women’s exclusion from the economic and public spheres in general. Today, women’s economic opportunities in the region are seriously constrained by the presence of gender-specific mandates establishing categories of gender-appropriate and inappropriate professions. In this context, in Women’s labour market participation in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Syria & Tunisia, Niels Spierings, professor at Radboud University in Nijmegen speaks of developing ‘opportunities’ through the role of gender equality laws and anti-discrimination laws for the elimination of persisting legal discrimination against women. In fact, gender equality can also be achieved by promoting affirmative action in order to restore formal equality through the establishment of quota laws for women in certain sectors and the passing of legislation that encourages women’s labor participation. The passing in 2002 of a landmark quota law requiring a minimum of 20% women in seats in the Moroccan parliament is one such example.

It is also important to focus on the role people themselves can play in the process by their adherence and capability to question their own attitudes and mentalities: Professor Neil Spierings describes “attitudes” as having to do with “whether the general societal norms in a country tolerate women to work outside the home”. Also, as Ivan Martin, Professor at European University Institute pertinently points out in Female Employment in Mediterranean Arab countries: Much More than an Economic Issue, “without the women’s contribution, there can be no change or development in the Arab Mediterranean countries”. Hence, women also need to stand up for their own rights and denounce the many sources of their everyday exploitation and ultimately claim their due.

About the writer:

Maha Tazi is a graduate in International Relations and Middle Eastern Politics from the University of Wollongong in Dubai (UOWD). She is currently working as a Project Consultant in Public Relations and Corporate Communications at APCO Worldwide and teaching part-time as an adjunct instructor in Philosophy at UOWD. Maha has a special interest in world affairs and gender issues: She took a Women Studies course for one year at Sciences Po Paris and worked with several civil society organizations which struggle for the advancement of women’s rights including Association Solidarite Feminine (ASF) in Morocco.

Maha Tazi is a graduate in International Relations and Middle Eastern Politics from the University of Wollongong in Dubai (UOWD). She is currently working as a Project Consultant in Public Relations and Corporate Communications at APCO Worldwide and teaching part-time as an adjunct instructor in Philosophy at UOWD. Maha has a special interest in world affairs and gender issues: She took a Women Studies course for one year at Sciences Po Paris and worked with several civil society organizations which struggle for the advancement of women’s rights including Association Solidarite Feminine (ASF) in Morocco.