What inspired you to become a lawyer, and when did you decide to pursue this career?

The career seemed to have decided on me instead *laughs*, actually I was enrolled in an accelerated A level programme in which the A level examinations had to be taken all in one year. One of my subjects was law and I scored 95% marks that year when the world distinction was awarded at 96% so for me, given that I had achieved the second highest score and that too within one year instead of the usual two, gave me a lot of confidence to continue and pursue law as a degree. However, from day one I was clear that I didn’t want to litigate. I was always more fascinated by the theory and by the academic indulgence this subject provided in context of and in relation to the society, state, citizen and rights so it really opened up my chances of studying these relationships within the legal and constitutional framework and that is what I do now also – study the legal profession and justice sector with a gender and inclusion lens based on primary data from our own context and studies in a bid to lead to transformative reforms.

What have been some of the most rewarding aspects of research in law, particularly as a female lawyer in Pakistan?

As a female legal researcher particularly on the subject that I have chosen to focus on – justice sector reforms with a gender and inclusion lens, I feel very excited about the kind of work I have been able to put together with regards to collection and presentation of data. As you know, lack of authentic data is one of our greatest challenges and no evidenced based policy and decisions can ensue without access to it so our work, whether in the form of the baseline report on state of representation of women in law 2020-21 or the gap analysis study on fair representation in justice sector has been able to really contribute to fill that data gap and through that work we have really been able to visualize the disparity and the sheer extent of the disparity of representation between men and women in the justice sector with several forums having zero percent of representation of women such as for instance the Judicial Commission of Pakistan and the Attorney General for Pakistan’s office. We have also been able to debunk the myths around women’s interest and commitment towards active legal practice and have shown through data that despite 95% of female lawyers reporting fear of being harassed in or while accessing courts, 75% of them would nevertheless still wish to pursue litigation and a career in judiciary. Thus really spelling out these gendered dynamics and dispelling the myths associated with it through hard data is really the most rewarding aspect of the kind of research I do in law.

As you are the founder of the Lahore education and research network. What is your vision when it comes to the LEARN initiative?

LEARN was established in the year 2015 with the aim to bridge the gap between legal education and practice via developing synergies and creating a network to connect the resources where they were needed. So for instance, we would act as intermediaries and connect potential trainees to trainers or mentors so that they could get the necessary support from bridging the gaps that our formal legal education system was not fulfilling at that time. We also design our own workshops and trainings under this forum and have held several conferences and dialogues for academic discourse in law as well.

What was the main inspiration or motivation behind launching the Woman in Law Pakistan initiative?

Women in Law initiative Pakistan evolved organically from the ‘women in law dialogue series’ which were an initiative of Lahore education and research network in 2016. The dialogue series was a three-part series of panel talks focusing on challenges and opportunities as well as non-traditional career options in law for women however, during the course of those conversations and the response it got from both, the men and women at that time was such that we all collectively felt that this really could not just be a three part dialogue and end there. We felt that this was something that needed a continued struggle and consistent engagement if we genuinely were serious about addressing the challenges and barriers that we came to consolidate and realize through these session that women faced in the profession because of their gender.

In 2020-21, you led the women in law collaborative project with the federal ministry of law and justice. So what did you achieve from that project?

The ‘Increasing Women’s Representation in Law’ was a project that we had proposed to the then Parliamentary Secretary of Federal Ministry of Law and Justice, Barrister Maleeka Bokhari who has been a source of inspiration and a champion leading from the front in terms of ensuring that the Ministry remained committed to this project and that it saw light of day despite very trying circumstances of Covid hitting us all unexpectedly and throwing all our plans and projections into frenzy. She enabled other partners to come on board and facilitate in the execution of the plans we had and we were so honoured to have had the support of Australian High Commission, British High Commission and Group Development Pakistan for it. Our purpose was to bring female lawyers out of the invisibility through positive actions and initiatives that could shine the spotlight on the brilliant work they do but which had no major platform to be showcased at. For this reason we proposed the following:

- Pakistan’s 1st ‘Women in Law’ awards hosted and supported by the Federal Ministry and other partners to honour and acknowledge female lawyers, practitioners, academics and even students as well as male allies and institutions that promoted gender diversity and inclusion; (see https://www.dawn.com/news/1660176)

- Symposium on fair representation in law to spark debate and create awareness on the disparity and the challenges associated with it amongst key stakeholders;

- Publication of Pakistan Journal of Diversity and Inclusion to create an academic space for featuring scholarly work on these themes; (see https://www.lawyher.pk/resources/PakistanJournal)

- Developing a one stop portal and mobile app for and about women in law by the name of lawyher.pk that would connect female lawyers to clients and opportunities, showcase their history and stories and give them a space to be featured and their work to be promoted;

- Publishing a baseline study of quantitative data on the state of women’s representation in law to fill the data gap and find out how many women actually are there in judiciary, prosecution, bar councils and as advocates. (see https://www.lawyher.pk/resources/Reports)

I am extremely happy to share that all five outcomes were achieved within the project duration of about a year and a half in a resounding way that paved the way for future work and set the standards and norms for how this work was supposed to continue. The awards enabled us to feature 71 nominees in 18 categories, the baseline report continues to be cited by Supreme Court Judges and other hi-profile stakeholders, while the portal continues to connect and showcase female lawyers and their work. Its impact continues beyond the life of the project and that for me is just the most rewarding aspect of this collaborative effort that would never have been possible without the support of everyone on board, including our advisory members at women in law, our media partners, Qanoondan and other key stakeholders and partners.

You have also worked with RSIL, how was your experience, the things you learn, or the achievements or struggles you would like to share?

Research Society of International Law (RSIL) was set up around 2003 or 2004 and I had the chance to intern with them in the summer of 2005, so it was still pretty early in the day and I was a student studying international law and human rights at that time so for me to be able to find a place where these areas were the focus of the legal and policy input as well as the research studies and fellowships or the trainings that RSIL aimed to conduct at that time was naturally a logical fit because I wanted a career in academia, in policy and RSIL was one of the only few spaces in Lahore at that time that offered this kind of opportunity and work. It has had incredible impact on the future trajectory of my career as I learned so much from RSIL that enabled me to create LEARN and Women in Law Initiative. In fact, it was my colleague Maira whom I had met at RSIL who later co-founded Women in Law initiative with me while she was here in Pakistan. Our executive director at that time Barrister Taimur Malik has been a huge source of support and guidance throughout my professional life. He shared that we must endeavor to find our niche to excel in our field and that is a life lesson that has really been very useful. My first international publication happened while I had returned to RSIL many years later as an associate in 2013, I got a chance to polish my writing skills and in conducting trainings, capacity building sessions and other academic debates a lot of which you can see being reflected in the work I do today as well so RSIL has definitely been a huge positive influence in my professional life.

You have done an in-depth study on recruitment and appointments in the justice sector. Why do you think that women’s representation is required in the justice sector? What impact it will form and how we can achieve that representation?

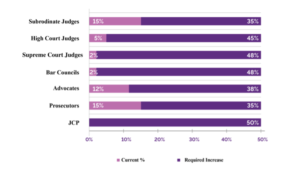

Women only make up about 15% of the judiciary in Pakistan. In higher courts, this is even less at 5% for high courts and 2% for Supreme Court. They only make barely two percent of members of Bar Councils. Overall there are 12% women as advocates in Pakistan but only 4% of them are advocates of the supreme court. This explains why there is no representation of women in Pakistan bar council which is the apex regulatory body of lawyers and the members are elected out of the pool of advocates of the supreme court so with such few numbers (only 4% women as advocates supreme courts) they hardly get a chance to be represented in the apex body. The judicial commission also has zero percent representation of women and this is the main body through which appointment of judges of the higher courts is made. So there is no doubt that the profession suffers from a representation problem, which gets worse when one looks at it from the additional lens of intersectionality as even fewer members of religious communities or differently abled persons or ethnicities etc get representation. The reason why representation is so important for the system and for the structures themselves is that society is not homogenous. Our society is rich in diversity and when people who make up the society do not end up seeing their own kind of people being reflected in the system, they lose confidence in the system and that directly impacts access to justice. As a result of homogeneity of male members that the judiciary is largely composed of, an entire jurisprudence and defence of ‘sudden provocation’ came to be developed in cases of killings in name of honour. Higher judiciary in particular is placed at a point where they contribute to jurisprudence and interpret laws and constitution that impact us all as citizens and as people so when half the population’s voices (women make up almost 50% of the population in Pakistan) and lived experiences do not get represented in the system, the system fails to benefit from that perspective and leads to decisions that leave so much to be desired in terms of fulfilment of fundamental rights. There have been studies to show that there is bias in homogeneity which can be off-set by diversity so the system should not be capable of ignoring lived experiences of half the population and must be seen to reflect that diversity for greater confidence in its outcomes or it loses its legitimacy.

This representation can only be achieved if the stakeholders commit to applying the gender and inclusion lens as the underlying objective of all their actions such that every time they have to send a list of nominations for appointments to higher judiciary, they should commit to endeavoring to send a balanced list that is as inclusive as it can be. Moreover, affirmative action in shape of addressing historical injustices that have held women back in the profession such as technical requirements that prioritize time spent in the profession or other technical requirements like number of judgements with your name as counsel should be revised in favour of more qualitative benchmarks, the pool of eligible candidates for appointment to judiciary should be widened to include in house legal counsels or even members from academia as in South Africa and UK etc and finally, there should be a legal and constitutional amendment that states that no single gender should comprise more than half of the composition of the bodies such the judicial commission etc.

How do you see gender stereotype in the legal profession? How can we tackle that?

Oh! there are plenty of stereotypes, from ‘you can’t practice, the court atmosphere is not for you’ to ‘why don’t you practice family law, criminal law would be a bit hardcore for you’ what is not a stereotype that women in law have not heard? The way to tackle them is to equip ourselves with more knowledge as being informed can really help us develop the confidence that we need to survive and respond to such tactics. I believe we now have more avenues or connecting with mentors and with one another to bridge some of those information gaps and Women in Law Initiative in particular is actively working to put out as much information and to render as much support it can to provide the information that young entrants look for in the profession so we invite them to reach out to us or to visit our pages and websites or even simply google or youtube information as now with a digital revolution in the legal profession, many LegalEd platforms like Qanoondan have also contributed significantly that ease access to information. Evidence and data debunking some of these myths is available in our own study on gaps in the recruitments and appointments processes so when a female law student or practitioner is more informed, more aware and more connected with her community of likeminded supportive mentors, she will be able to navigate these stereotypical assertions designed to discourage and hold women back in a much better way.

What barriers do you see in our legal system? Initially at the start of your career did you feel hindrance or consider it challenging to perform litigation in court?

I did try litigation initially which only reconfirmed to me that it was not for me, not because I can’t do it, it isn’t hard, in fact with the quality that usually is around, it isn’t even hard to actually stand out as good and that can happen soon enough but the way the system is structured and in how it guarantees no basic labour rights even, no timings, no routine, no minimum wages, no parental leaves, day care or flexible work hours, shows that it is a profession that is highly exploitative. When coupled with gender based discrimination designed to make a woman work behind the scenes on research and case preparation in offices without much of a chance to argue or be present in the court herself to have her presence and attendance marked that could get her those technical requirements of judgments with her name as counsel or co-counsel for meeting the criteria to apply for license of advocate supreme court or from thereon as a candidate for Pakistan bar council election etc; the exploitation and discrimination becomes a serious barrier that hinders advancement of women in the profession in senior and decision making roles.

In your experience, what are some of the most common challenges that female lawyers in Pakistan face?

The most common challenges women face start from early discouragement at home and in schools from active legal practice, which is kept as the base for future advancement in the profession and so this discouragement inadvertently or advertently feeds into loss of opportunity for women to excel in this field. They find it harder to access jobs in law firms and when they do, they are met with sexist questions in interviews ranging from their marriage and family plans to being made to stay at offices and do background work that doesn’t help much with meeting the technical requirements for advancement in the profession. When a male associate leaves a firm to start his own practice, that is looked upon as upward mobility and may even be celebrated with a cake over tea in the office but when a female associate leaves the same firm for marriage, that is held against not just her but the entire gender even though it is a role that the society expects her to play but doesn’t support her by creating enabling structures that can enable her to retain her role both at home and at work. Young lawyers are hardly ever paid and when they are, the amounts are paltry so access to internships and work opportunities becomes a question of who can afford to get to them. Women remain invisible to men and the arbitrary powers vested in male dominated institutions or male centered laws and processes that do not take into account the gender perspective always disproportionately impact chances of women from advancing in the profession. We have already talked about how technical and quantitative requirements may serve as a gate keeping tactic to hold women back from advancing. Harassment and even direct physical violence has also been directed at female lawyers so safety and safe access to work places are both real challenges for women. It is difficult to address these concerns within the existing system that suffers from ‘regulatory capture’ where regulators (the bar) being dependent upon the votes of the lawyers is unable to effectively exercise disciplinary control over them.

What is the Role of women in the legal profession and what contributions they have made?

The role of women in legal profession is really mostly the role of any professional lawyer however, having said so, the women do indeed by virtue of their unique or lived experiences add value to the discourse, jurisprudence and developments in law so they bring in something on the table which improves the quality of justice for a wider class of persons. For instance, in the 1994 Shehla Zia v Wapda case, the petitioner was successful in reading the right to clean environment as part and parcel of the right to life in our law at a time when environmental law, sustainable development and SDGs were not as mainstreamed as they are now. In another more recent case, Sana Khurshid a differently abled law student turned practitioner and petitioner filed for accessibility rights after which a law was passed to ensure that all public building would have ramps and access for differently abled persons. Female practitioners and a female judge became catalyst in banning the unscientific two finger test in rape cases for women as being unconstitutional and against dignity of a woman in the Sadaf Aziz v Federation of Pakistan case. Women lawyers gave valuable input to the key amendments in the workplace harassment law at the federal level which were passed by the assemblies in January 2022 that enabled home-based workers to also bring proceedings under the law amongst other developments. In short, women’s contribution towards fundamental rights, access, inclusion and towards creating a more dignified society for all through legislative inputs or litigation are contributions that have impact beyond individual cases and we must not only remember them but also acknowledge and celebrate and take them forward.

What is your specific area of interest in law? As I saw your profile you have an interest in human rights and environmental laws. So how do you see the current climate issues particularly in Pakistan as the air quality index in Karachi and Lahore is worst and what steps we can take to tackle that issue?

I love looking at the justice sector with a gender and inclusion lens. For me, research on various aspects of legal profession in that context are very exciting and we have discovered so much in the process because to be able to reform anything we must first understand them so my work allows me to really get into the depth of all things, like how the interviews for license to practice as advocates are structured, how they may be discriminatory or arbitrary, how the legal education reform through courts was problematic, what the state of women’s representation is, whether it has any enabling structures in place or not are all questions that really instantly connect with me because I feel they have such a huge impact on everyone who gets enrolled into this degree but also public at large who have to also deal with impact of the judgements and structures that they come in contact with while accessing rights in the system. Environment law and climate justice is a huge area of interest for similar reasons because it impacts more than just the litigant, it impacts us all, our children so how can the law help? What did other countries do when they faced similar crisis in terms of law? Are all questions that deeply interest me. However, since I am not a practitioner myself, I have played my part through creating awareness on climate justice and rights, the treaties we have signed in this regard and what our own laws say about it through the climate action Pakistan platform. in particular, war on smog has been a huge focus since Lahore, where I live is amongst the most polluted cities in the world and I live through that toxicity each day of my life along with the children whom I see suffer so much due to risks associated with smog. From the studies we know that transport and fossil fuels are a huge contributor to our smog woes and the only way to reverse it is to rethink our development paradigm, to rethink how we design our cities and to replace private cars with efficient, safe and effective public transportation network that can enable us to get rid of our dependency on private cars, leave more space to restore pedestrian and green spaces on roads. We must also check the urban sprawl in Lahore in particular.

You also wrote debut short story features in an anthology on stories from the pandemic by liberty books Pakistan. Also, you wrote about the patriarchy in politics and political parties in Pakistan. Tell is more about that, the creative process?

So the stories from pandemic had one of the stories in the collection that I had also contributed. It happened when one of the editors, Sana Munir gave me the opportunity to write considering she knew I was always interested in writing a creative novel so she was kind enough to offer me an opportunity that required a shorter commitment to see how it goes for me. I loved the format and the context – covid 19 within which we had to express ourselves and she gave us authors complete freedom to interpret the pandemic and project it how we each experienced it or thought about it. I wanted to focus on the alienation of patients, on the fact that it saw no age barrier and could impact a young cis gender male who was my protagonist just as much as any other person, I wanted to also show how such a life changing emergency can enable people to rethink their priorities in life and to realign themselves with greater social good and all these themes came through in my story. I’m very grateful for that chance. The patriarchy in Politics and Political Parties in Pakistan is however not a creative endeavor. It was a research-based paper commissioned by Friedrich Ebert Stiftung and I used primary data techniques of survey and interviews as well as secondary research through literature to highlight how patriarchy may impact representation and presence of women in politics and how that can be addressed going forward.

We are excited about your new publication, please tell us about it?

Patriarchy is a system of relationships, associations, beliefs, and values or ethics embedded in political, social, and economic systems that lead to gender-based discrimination between men and women in all walks of life. This publication addresses patriarchy at the level of politics in the context of Pakistan. The Pakistani female politicians in spite of many hurdles and challenges in a typical male dominated setup, have been not less than their male counterparts when it comes to delivering at work including legislations, running political campaigns and their bold presence in public spheres. However, the integrated patriarchal norms pose serious issues and challenges to their work. Looking at how patriarchy impacts women in politics in terms of their access, growth and stature as well as their reputation and position was therefore the focus of this paper as well. It attempted to look at these issues at various degrees of intersectionality where it could and attempted to bring together diverse experiences of different female politicians operating at different stages, different age groups and different religious or income brackets. It is hoped that this paper would provide a first step in the direction of understanding the dynamics of patriarchy at different tiers of government and thoughtfulness on why such patterns exist and how they can be dealt with. It is also hoped that it might contribute to a further development and strengthening of the idea of necessity of enabling environment for women to be in politics so that they can play their roles the best of themselves.

You also wish to uplift the writing industry in Pakistan as you are one of the founding members of the Authors Alliance PK. What motivation leads you towards this project and what impact this initiative will create?

The writing industry has a lot of potential and coming from a family whose background is rooted in arts and media and who loves to read and write herself, it was not unnatural for me to turn my love for reading and writing into seeing the potential for its growth as an industry that can benefit the authors, the showbusiness and Pakistan’s dwindling economy as a whole even. Great productions begin with great stories and since I had a background in law, it was appalling to find out how piracy was impacting our writers and their rights. In any case there are no formal royalties as such, on top of it, plagiarism and piracy are so common and with book bans, access to quality books was reducing day by day. For a book lover, that is the worst nightmare and so authors alliance really grew out of a desire of us writers and publishers to really foreground the concerns of authors and publishers as a community as well as a stakeholder with potential to turn around the economy if supported correctly by our authorities. We also use this platform to showcase young Pakistani talent and promote their work free of charge.

Most importantly, how do you balance your personal and professional life as a female lawyer with these great projects and works?

By not keeping myself bound to brick and mortar traditional workplace and by maintaining my flexible work routine as a self-employed-work-from-anywhere kind of person with the ability and authority to decide for myself when and how much is it that I want to work and where and how to complete that. I can this because it does come from a place of privilege and I am aware of that however, flexible work does not mean less work. In fatc, without the discipline of committing to a flexible work routine that is extremely demanding, because there is multitasking and constant juggling, it just wouldn’t be possible. When my son was younger, I worked less and preferred adjunct teaching positions that required less time away from home, as my son grew up, I became more able to manage my time, especially when he started school. I also worked hard to get support in shape shared responsibilities at home when it comes to our child so that my work can be accommodated in event of any pressing commitments that cannot be moved around say during school run. I used to work from home when it wasn’t even cool and there was no zoom, now it’s much easier, at times even preferred and Zoom is a great addition to the tools I use to manage so much of what I do.

Last but not least, what advice would you give to other women who are interested in pursuing a career in law in Pakistan?

Information is your best friend so try and be as informed about processes and procedural or technical requirements for advancement so that you do not lose out on any precious time as a result of not being aware of any technicalities. This may not always be easy but asking for support and assistance usually does go a long way so don’t shy away from reaching out to people for it.

Alishba Fazal-ur-Rehman is currently enrolled in the fifth semester of LLB at Ziauddin University, Karachi. She is also a research associate at the Ziauddin University, Center for Law and Technology, and an intern at Climate and environment initiative (CEI) at the Research Society for international law (RSIL). She has done research on Data Protection and Cyber Security in Pakistan and written blogs on the current issues of Pakistan in order to develop the state through different practical measures. Being a Law aspirant, she is consistently battling Pakistan’s socio-cultural norms to engage with more growth-enabling opportunities.