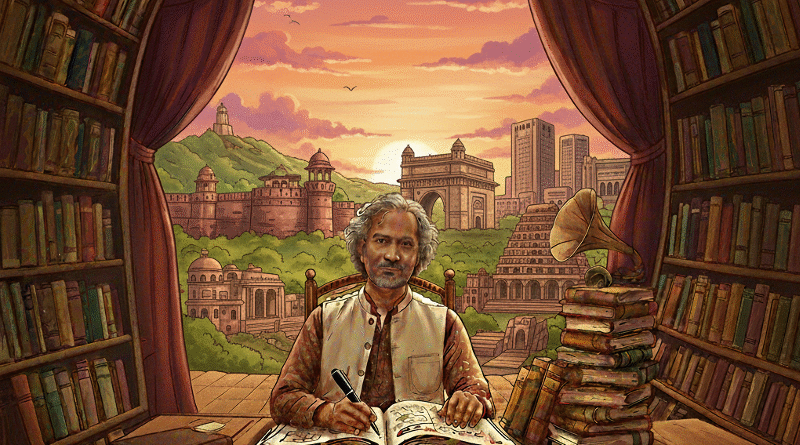

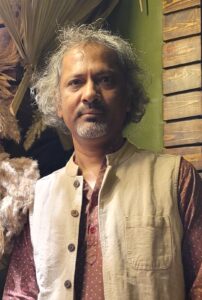

Rahman Abbas is the winner of India’s highest literary award, the Sahitya Akademi Award, for his fourth novel, Rohzin in 2018. He is the author of eleven books, including seven novels. Rahman has also won four State Akademi Awards. His writings have been translated into English, German, French, Hindi, and discussed in Arabic, Konkani, Marathi, Assamese & other languages. The German translation of Rohzin was discussed in Switzerland as part of ‘The Days of Indian Literature’ in February 2018. He toured Europe thrice to discuss his writings and do novel related research. Penguin Random House India has published Rohzin in English in May 2022, and the novel was long-listed for the JCB Prize and shortlisted for the Muse India 2023 GSP Rao Translation Award. Penguin India has also published On the Other Side (Urdu title: Khuda Ke Saaye Mein Aankh Micholi) in June-2024.

Be it art, literature, cinema or theatre, freedom of expression and artistic expression have been more than just occasionally charged with the notion of obscenity. Can truth be obscene? What does obscenity imply especially in the multipolar world we live in today? How do we evaluate obscenity?

The intolerance of a society is reflected in what it labels as obscene in art and literature. But this notion doesn’t arise on its own, like a plant sprouting from the soil. Rather, it is shaped by puritans—political and religious pressure groups that seek to control society and force it to conform to their ideas of good and evil. The truth remains the truth, even if it appears obscene for some. However, it cannot be imposed upon others within a predetermined timeframe; rather, one must allow space for their intellectual and cultural maturation. Societies are not static entities—they grow and evolve, much like trees. Nations and cultures, too, undergo transformation over time. What was once deemed obscene in Europe and the United States—such as the writings of D. H. Lawrence and James Joyce—is now recognized for its literary significance. In today’s multipolar world, the boundaries of what is considered acceptable have further diminished, especially in an era where everything is accessible via mobile screens. As a result, concerns regarding obscenity in art and literature have become increasingly irrelevant to contemporary readers. There is no permanent or a fix parameter to evaluate obscenity in literature. A passage that is artistic to one person might be deemed obscene by another.

Rahman Abbas

History is replete with examples when it comes to obscenity trials on literary texts. In the movie (and real life of course) Manto the famed writer on trial challenges the notion of obscenity by explaining that his writing merely mirrors society. What in your opinion is the outcome of such trials, be they redemptive or vice versa? Juxtaposing creative freedom and censorship, the question also arises if the real legal outcome is more important or the legal course, the legal journey, the trial itself, that takes place?

Yes, there have been many incidents and trials. Sadat Hassan Manto and Ismat Chughtai are prime examples of the farcical attempts to silence creativity. However, history shows that those who accused them of writing obscene short stories have long been forgotten, while Manto and Ismat remain among our most beloved authors. These trials often hurt writers economically and alienate them from their societies. Sometimes, they put restrictions—but they also teach writers a great deal about the very societies they were born to write about. In a way, the outcome of such trials is important, as we’ve seen in the cases against Manto and Ismat. In most instances, the courts have upheld the right to freedom of expression, and those who tried to deface literature have been defeated. The journey through these trials becomes part of the larger history of the fight for freedom of expression, inspiring future generations of authors to reflect on themselves and continue the struggle for free thought

What is the role and value of artistic freedom and freedom of expression where the fodder for the masses is fear, a wedge that triggers hate, othering and multipolarity? Where even freedom of expression is under fire.

That is what this house has always been—a place of hostile Homo sapiens. The desire to rule over the masses is the root cause behind the birth of religions, nationalism, and many other -isms. The masses have always been controlled with an iron hand, instilling fear in them by those who hold power. Fear, used as a trigger to create “the other” and keep people divided—by caste, sect, color, language, and identity—is also a common tool of authoritarian rulers. In such a world, the role of artistic freedom and freedom of expression becomes even more significant. As Faiz Ahmed Faiz once wrote:

jalva-gāh-e-visāl kī sham.eñ

vo bujhā bhī chuke agar to kyā

chāñd ko gul kareñ to ham jāneñ

This moonlight, metaphorically, is the light of humanity—of continuity and of the future. It is what gives us hope and pushes us to continue the struggle for a better world. Sometimes it feels like a dream—that this place will one day be truly free, that all will be equal, and there will be no brutality, no violence, no hate crimes. But even if it is just a dream, it is the mother of all creativity. This dream is a sign that Homo sapiens still have the will to survive and strive for a better tomorrow.

Reading one of the reviews of your book (On the Other Side), where the reviewer talks about the ‘dangers of the divisiveness of religion’ – do you think it is divisiveness or the politics of religion leveraged by different ‘actors’, our belief systems, patriarchy, hegemonic socialization that are deeply entrenched in us as individuals as well as society as a whole?

Yes. in fact, it is the politics of religion—but in its culminative nature, it becomes dangerously divisive. The other agencies you mentioned also bear the heavy burden of religious politics. It seems that ideas, thoughts, and reactions often merely reflect the hues of a religion that has been politicized to sway the masses.

Do you think art imitating life is a subversive act?

II do not believe that art merely imitates life; rather, art perceives life through a different lens in order to understand it and its underlying realities. This process is not one of imitation, but of intervention. Whether this act constitutes subversion is difficult for me to determine—I have not lived enough lives to claim the authority to judge it.

How can storytelling bear witness to oppression and awaken collective conscience?

Yes, this is one of the essential functions of literature. Progressive Urdu literature and Dalit literature stand as powerful examples of how storytelling bears witness to oppression—by giving voice to those historically silenced. Likewise, Latin American novels often reveal the wounds left by colonialism or expose the mechanisms through which dictatorships stifled dissent. These literary works become archives of suffering, and returning to them has the potential to stir the conscience. Literature does more than record pain; it resists. Writing holds the power to challenge dominant narratives—those constructed by states, political regimes, or theocratic authorities. In contrast, art affirms democratic values, celebrates freedom, and stands in opposition to tyranny. There are many ways to bear witness to injustice, cruelty, and oppression. Each storyteller, guided by their own vision and conviction, chooses their path—if they choose to speak at all.