May 18th, 2020, Bangkok (Thailand): The Government of Bangladesh should utilize existing quarantine facilities for Rohingya refugees potentially exposed to COVID-19 and suspend its use of Bhasan Char island for refugees, said Fortify Rights on May 15th, 2020. Bangladesh authorities confirmed yesterday the first case of COVID-19 in the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar District.

Bangladesh authorities are currently holding in quarantine at least 300 Rohingya refugees on Bhasan Char, a poorly equipped, flood-prone island located off the coast of mainland Bangladesh.

“The government should do everything in its power to prevent an outbreak,” said Matthew Smith, Chief Executive Officer at Fortify Rights. “Bhasan Char is not a viable option for any COVID-19 response.”

On May 7, the Bangladesh Navy transferred to Bhasan Char Rohingya survivors found on board a ship adrift in the Bay of Bengal. Five days earlier, on May 2, Bangladesh authorities detained and transferred to the island 29 Rohingya survivors who escaped from a ship after making payments to the traffickers in exchange for their release.

Fortify Rights believes that at least one more ship with up to 500 Rohingya refugees on board remains stranded at sea.

On May 2, Bangladesh Foreign Minister A. K. Abdul Momen announced to the media, “Any new Rohingyas, if there are, will be sheltered at the Bhasan Char.”

Fortify Rights interviewed a Rohingya survivor and four family members of survivors sent to Bhasan Char on May 2 as well as humanitarian aid workers.

“My daughters are now on Bhasan Char,” said “H.K.,” a Rohingya father in Kutupalong camp. “They told me [by mobile phone] they are having difficulties and they were crying. They said they are very much afraid to stay [on the island].”

The Government of Bangladesh first proposed the idea to relocate Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char in 2015. Dhaka eventually developed the island and planned to relocate refugees beginning in 2018 but repeatedly postponed relocation plans after consistent outcry and concern from Rohingya, governments, U.N. experts, and human rights and humanitarian organizations. In an open letter to Prime Minister Sheik Hasina on November 12, 2019, Fortify Rights and 38 other organizations called on the government to facilitate a U.N. technical assessment to ensure the arrangements on the island meet international standards before proceeding with relocations. The government has yet to facilitate such an assessment and questions remain about the arrangements on the island.

H.K. told Fortify Rights he paid to send his 19 and 17-year-old daughters to Malaysia for marriage. However, Malaysian authorities intercepted the ship and pushed it back out to sea. His daughters spent several weeks held in captivity on the ship before being released by traffickers on the ship.

H.K. told Fortify Rights how he paid for the release of his daughters: “The broker began collecting money from families [in the camp] saying those who will pay money will be prioritized to bring their relatives from the boat. I had to pay a total amount of 120,000 Taka [US$1,400] to bring my daughters back.”

He explained how the authorities caught his daughters as the traffickers were bringing them to shore: “It was muddy on the river bank [where the authorities caught them]. Those who were strong could manage to escape there and the remaining people got caught [by authorities] . . . There were a total number of 29 people taken to Bhasan Char [on May 2].”

Some Rohingya refugees released by the traffickers on May 2 evaded the authorities and returned to the refugee camp. One such 18-year-old Rohingya survivor told Fortify Rights how camp authorities directed him to go to a transit center on the mainland for a two-week quarantine period.

“I could have stayed at my home without coming to the transit center,” he said. “However, the CiC [Camp-in-Charge–the Bangladesh officials overseeing the administration of the Rohingya refugee camps] informed us to come to the transit camp [for quarantine].”

On May 5, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)—the U.N. agency mandated to protect refugees—said: “[A]ll preparations [are] in place to ensure the safe quarantine of any refugees arriving by boat to Cox’s Bazar, as a precautionary measure related to the Covid-19 pandemic.” UNHCR said this includes “full medical screening, for the required 14-day quarantine period at designated quarantine centres.”

An international aid worker told Fortify Rights that the recent survivors show signs of “serious mental stress and trauma.”

Fortify Rights documented killings, beatings, and deprivation of food and water by traffickers on board a ship carrying Rohingya refugees that returned to Bangladesh on April 15. The ship spent nearly two months adrift at sea, and survivors reported witnessing dozens of deaths.

When governments push ships of refugees back out to sea, they violate the principal of non-refoulement, which prohibits the “rejection at the frontier, interception and indirect refoulement” of individuals at risk of persecution. While Bangladesh and other regional governments have not ratified the 1951 UN Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, the principle of non-refoulement is part of customary international law and is therefore binding on all states. Under this principle, all countries are obligated to protect Rohingya from being returned, including through returns that are informal, such as pushbacks out to sea.

The governments of Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Thailand are members of the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime, which includes a commitment for states to cooperate in combatting human trafficking and states that, “in all cases, the principle of non-refoulement should be strictly respected.”

Regional governments should deploy search and rescue missions for ships adrift at sea and ensure the safe disembarkation of survivors, said Fortify Rights. Governments should also investigate and prosecute human traffickers preying on Rohingya refugees.

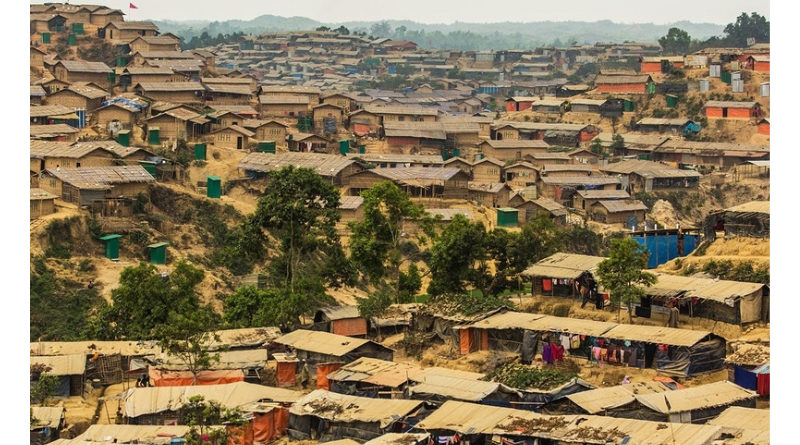

More than a million Rohingya refugees, many of whom fled genocidal attacks by the Myanmar military in 2016 and 2017, live in overcrowded refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar District, Bangladesh. In October 2019, Fortify Rights documented how Bangladesh authorities included Rohingya refugees on official lists for relocation to Bhasan Char island without consulting those on the list about the plan or their willingness to move to the island.

Since September 2019, the Government of Bangladesh has restricted mobile internet communications in areas around the refugee camps, limiting access to vital public-health information. These restrictions coupled with the construction of fencing to confine refugees to the camps has heightened fear among Rohingya, particularly given concerns around COVID-19.

“The authorities should urgently support preparations for more COVID-19 cases, ensure unfettered access for aid groups, and restore internet connectivity for Rohingya and nearby host communities,” said Matthew Smith. “Public health and human rights go hand-in-hand.”

Image: UN, OCHA/Vincent Tremeau