This article is part of Ananke's Resilience Edition published on ISSUU - the special edition can be viewed here.

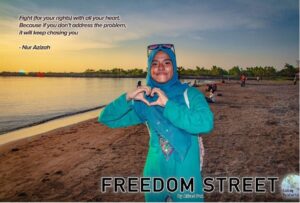

“Fight for your rights with all your heart. Because if you do not address the problem, it will keep chasing you” ~ Nur Azizah – Rohingya Refugee

Sex based discrimination being the stark reality that it is for most women and girls globally, means that refugee women and girls who already exist within a marginalised and vulnerable global community are faced with compounded marginalisation within their already marginalised community simply because they are women and girls. The overwhelming majority of refugee women and girls are hosted by low and middle-income countries, and these women and girls are burdened with persistent and systematic gender inequalities. The ordinary experiences that shape women’s and girls’ everyday lives throughout the world are compounded for those who are refugees and/or are stateless. UN Women explains that refugee and migrant women’s voices are often missing from policies designed to protect and assist them. The absence of a gender perspective in policies, frameworks, and responses impairs efforts to protect refugee women and girls, hindering their ability to realise their full potential and live with dignity. Women and girls’ access to legal protection, basic services and the labour market are affected by multiple factors which depending on the specific country context, may include discriminatory regulations, uneven and biased implementation of regulations, xenophobia, and racism. The onset of the global pandemic has amplified and exacerbated invisible as well as pre-existing biases, inequities, and vulnerabilities. Specific concerns for refugees and asylum seekers during the pandemic include maintaining safety measures in overcrowded camps and detention centres; lack of access to countries of asylum or resettlement due to border closures; and lack of income support for those who have lost their jobs. A pandemic of this nature, that is unprecedented in our life-times, brings great uncertainty and fear for all of us, but especially the people who are most vulnerable in our societies. The World Health Organisation articulates that the COVID-19 pandemic has shown us the consequences of vulnerability, with increased rates of infection and deaths amongst the poor and the disadvantaged, including refugees and migrants. Evidence suggests that during the COVID-19 pandemic, refugees and migrants have experienced high levels of xenophobia, racism, and stigmatisation. All these vulnerabilities have been further exacerbated by public health control measures and border closures. The 2021 Global Gender Gap Report reveals that progress to gender equality has been set back because of the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore it is vital that recovery plans focus on gender inclusivity.

The Story of Nur Azizah – Gender Dynamics of a Refugee Woman

Nur Azizah was born in Malaysia on October 2, 2001, as an unwanted child by a stateless family and having no identity herself. At just 19 years of age, Azizah has faced significant hardships and challenges throughout her life. Many of the hardships and challenges Azizah has been confronted with have happened whilst she was a child and adolescent. Recognition of the gendered experience of refugee women and girls is necessary and should not be ignored because of their vulnerability to exploitation, trafficking, discrimination, and different forms of violence. Women and girls are exposed to forms of violence related to their gender, their cultural and socio-economic position, and the legal status among other factors. Whilst it is true that women and girls in displacement are often confronted with dangerous and complex circumstances, they also display extraordinary agency and coping strategies that are vital to handling the circumstances they find themselves in and to also improve their living conditions. Azizah grew up without her mother in her life and was abandoned by her stepmother. Azizah’s lack of protection as a refugee has meant that she has married at a young age. Azizah is a stateless Rohingya-Karen refugee based in Makassar, Indonesia who has attempted to come to Australia to seek refuge with her family. Refugees in Indonesia are not permitted to study, work, travel beyond city limits, marry freely, or contribute to Indonesian society. Most refugees in Indonesia were bound for Australia and have experienced significant unjust treatment, whilst fighting every day for their survival and their future. Quite often in Australia we only hear the voices and perspectives of male refugees, and therefore to hear the voice of a young refugee woman who is not afraid to speak her truth is crucial for Australian society to better understand their needs and experiences. Refugee women’s voices are often silenced, and their capacity ignored. Their contributions and solutions go unrecognised because their capabilities and social capital are devalued. Azizah is an extraordinarily self-determined young woman who aspires to study despite not ever attending formal schooling. Despite the significant challenges that have dominated Azizah’s life, she is determined to make a life for herself and is extremely confident in raising her voice and sharing her experiences as a female child refugee.

Nur Azizah was born in Malaysia on October 2, 2001, as an unwanted child by a stateless family and having no identity herself. At just 19 years of age, Azizah has faced significant hardships and challenges throughout her life. Many of the hardships and challenges Azizah has been confronted with have happened whilst she was a child and adolescent. Recognition of the gendered experience of refugee women and girls is necessary and should not be ignored because of their vulnerability to exploitation, trafficking, discrimination, and different forms of violence. Women and girls are exposed to forms of violence related to their gender, their cultural and socio-economic position, and the legal status among other factors. Whilst it is true that women and girls in displacement are often confronted with dangerous and complex circumstances, they also display extraordinary agency and coping strategies that are vital to handling the circumstances they find themselves in and to also improve their living conditions. Azizah grew up without her mother in her life and was abandoned by her stepmother. Azizah’s lack of protection as a refugee has meant that she has married at a young age. Azizah is a stateless Rohingya-Karen refugee based in Makassar, Indonesia who has attempted to come to Australia to seek refuge with her family. Refugees in Indonesia are not permitted to study, work, travel beyond city limits, marry freely, or contribute to Indonesian society. Most refugees in Indonesia were bound for Australia and have experienced significant unjust treatment, whilst fighting every day for their survival and their future. Quite often in Australia we only hear the voices and perspectives of male refugees, and therefore to hear the voice of a young refugee woman who is not afraid to speak her truth is crucial for Australian society to better understand their needs and experiences. Refugee women’s voices are often silenced, and their capacity ignored. Their contributions and solutions go unrecognised because their capabilities and social capital are devalued. Azizah is an extraordinarily self-determined young woman who aspires to study despite not ever attending formal schooling. Despite the significant challenges that have dominated Azizah’s life, she is determined to make a life for herself and is extremely confident in raising her voice and sharing her experiences as a female child refugee.

Melanie Bublyk, Ananke’s Human Rights Advisor spoke with Nur Azizah about her experiences as a female child born into statelessness and the obstacles she has faced growing up as a female refugee.

In 2010 when I was around nine years old, my father was intercepted by Indonesian officials and detained because he was entering Indonesia illegally from Malaysia. I was left in the care of my stepmother in Malaysia, where she abandoned me and left me on the road. Because I have no citizenship, I had no education growing up. I did not attend primary or high school. It was hard growing up because of my situation. Because I do not belong anywhere, I had no rights to study, work, travel, marry, practice my religion. My identity as a stateless person meant that wherever I tried to find refuge, I would always be locked up in detention. My family had no choice but to leave their homeland in Myanmar because of the persecution that they endured. They hoped that they could find a home where they would be safe and live-in peace and with dignity. Because Malaysia and Indonesia have not signed the UN Convention for Refugees, it means that our rights are not protected and there are no laws to protect us. My hopes and dreams are to have a better future, study, help others especially refugees and most importantly to have citizenship. I guess that means to be seen as a human being and live a normal life where I belong to and am included in a community and society at large as a fully-fledged citizen.

Alfred Pek is a filmmaker, Videographer Journalist and a refugee advocate based in Sydney Australia. He has been working on a documentary called “Freedom Street”. The documentary includes the story of Azizah as well as Joniad and Ashfaq. The three of them have been stuck in limbo in Makassar, Indonesia for several years because of Australia’s border policy. Since 2013, there are currently around 14000 refugees in Indonesia and every day their hopes for resettlement are diminishing. Freedom Street presents the refugees’ stories while deconstructing Australian policy in a series of conversations with various experts.

The experts provide insight into Australia’s long history of border control and Australian-Indonesian relations which serve to contextualise the struggle of our three protagonists as they look towards an uncertain future. The documentary highlights the cost of Australia’s undemocratic policies both on the refugees and the Australian taxpayer while urgently sounding the alarm for meaningful and humane solutions to an ever-worsening issue. Just like Manus, Nauru, and the various mainland detentions. Refugees’ lives are on hold and their future is uncertain in Indonesia directly because of Australia’s strict border policy. These refugees have no rights, and this means that they cannot attend school or work and they have extraordinarily little chance of resettlement. These are directly because of policies and the context goes much further beyond Manus and Nauru.

Alfred explains that “For too long, we have not had a comprehensive film project and articles that contextually explained Australia’s entire refugee policy history in the Asia-Pacific region, touching upon our immigration history as well as our changing attitudes towards refugees over time. Manus and Nauru (and the various mainland detention centres) in retrospect are seen because of a contextually much larger issue that we have faced in the region sadly.Our end goal for why this film is being created is to create an effective tool that advocates for the rights of refugees and so that changemakers, social justice campaigners and progressive communities in general can utilise our work in their advocacy efforts”.

You can learn about the backgrounds of the film here:

https://rightnow.org.au/opinion-3/freedom-street/

https://theaimn.com/freedom-street-an-immigrants-journey-into-australias-border-protection-cruelty/

Website: www.freedomstreetfilm.com

Freedom Street has been a self-funded project and you can support the work of Freedom Street Documentary by visiting:

https://documentaryaustralia.com.au/project/freedom-street/